Previous chapter - Overview - Appendices - Next Chapter

Let’s see if we can turn hecto into a text viewer in this chapter.

A line viewer

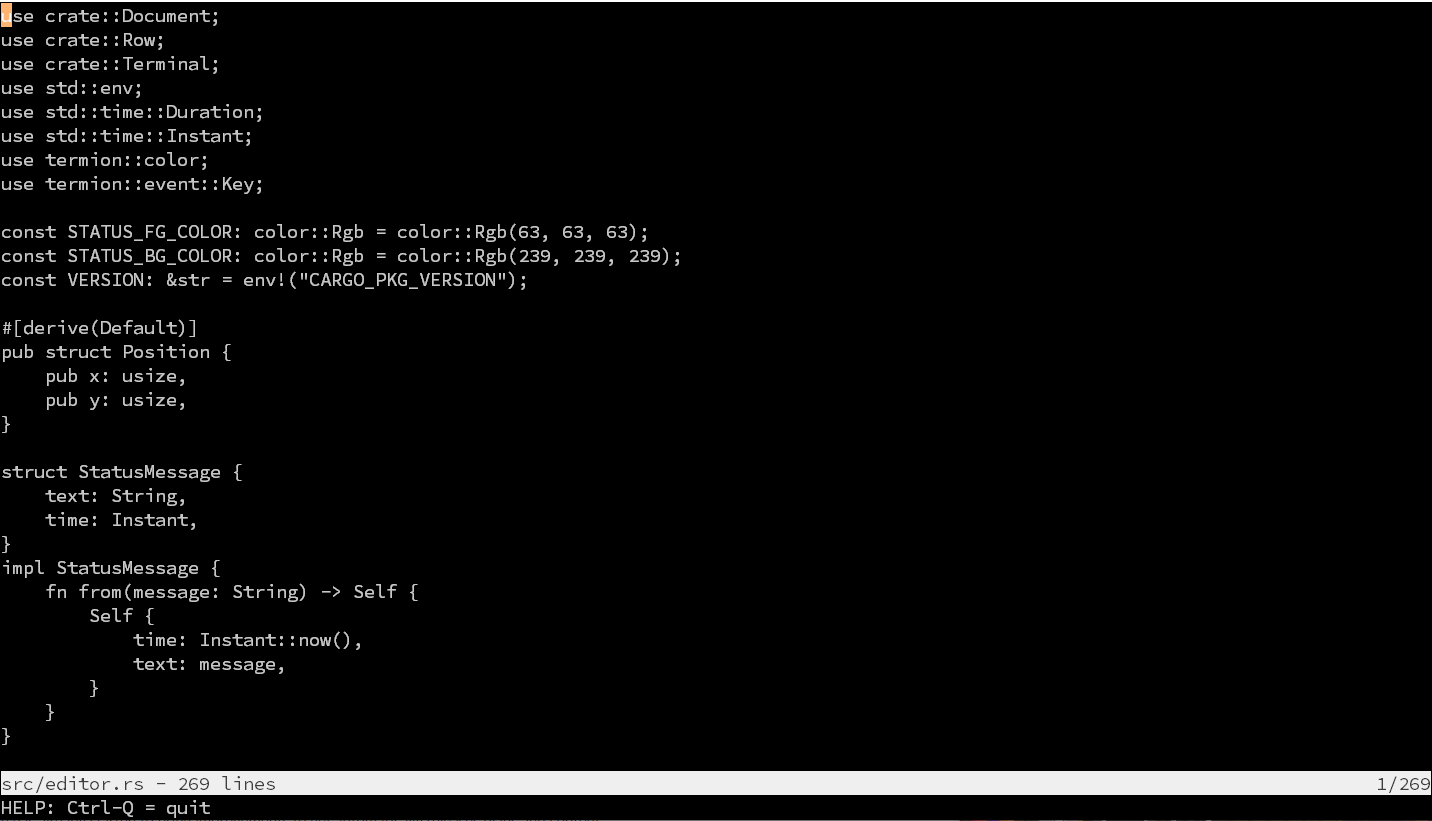

We need a few more data structures: A Document which will represent the

document the user is currently editing, as well as a Row in that document.

|

@@ -0,0 +1,6 @@

|

|

|

1

|

+

use crate::Row;

|

|

2

|

+

|

|

3

|

+

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

4

|

+

pub struct Document {

|

|

5

|

+

rows: Vec<Row>,

|

|

6

|

+

}

|

|

@@ -1,3 +1,4 @@

|

|

|

1

|

+

use crate::Document;

|

|

1

2

|

use crate::Terminal;

|

|

2

3

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

3

4

|

|

|

@@ -12,6 +13,7 @@ pub struct Editor {

|

|

|

12

13

|

should_quit: bool,

|

|

13

14

|

terminal: Terminal,

|

|

14

15

|

cursor_position: Position,

|

|

16

|

+

document: Document,

|

|

15

17

|

}

|

|

16

18

|

|

|

17

19

|

impl Editor {

|

|

@@ -32,6 +34,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

32

34

|

Self {

|

|

33

35

|

should_quit: false,

|

|

34

36

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

37

|

+

document: Document::default(),

|

|

35

38

|

cursor_position: Position { x: 0, y: 0 },

|

|

36

39

|

}

|

|

37

40

|

}

|

|

@@ -1,9 +1,13 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

#![warn(clippy::all, clippy::pedantic)]

|

|

2

|

+

mod document;

|

|

2

3

|

mod editor;

|

|

4

|

+

mod row;

|

|

3

5

|

mod terminal;

|

|

6

|

+

pub use document::Document;

|

|

4

7

|

use editor::Editor;

|

|

5

|

-

pub use terminal::Terminal;

|

|

6

8

|

pub use editor::Position;

|

|

9

|

+

pub use row::Row;

|

|

10

|

+

pub use terminal::Terminal;

|

|

7

11

|

|

|

8

12

|

fn main() {

|

|

9

13

|

Editor::default().run();

|

|

@@ -0,0 +1,3 @@

|

|

|

1

|

+

pub struct Row {

|

|

2

|

+

string: String

|

|

3

|

+

}

|

In this change, we have introduced two new concepts to our code: First, we are

using a data structure called a Vector which will hold our rows. A Vector is a

dynamic structure: It can grow and shrink on runtime, as we are adding to or

removing from it. The syntax Vec<Row> means that this vector will hold entries

of the type Row.

The other new concept is this line:

#[derive(Default)]

It means that the rust compiler is supposed to derive an implementation for

default. default is supposed to return a struct with its contents

initialized to a default value - which is something that the compiler can do for

us. With that directive, we do not need to implement default ourselves. Let’s

see if we can simplify our existing code with it:

|

@@ -4,6 +4,7 @@ use termion::event::Key;

|

|

|

4

4

|

|

|

5

5

|

const VERSION: &str = env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION");

|

|

6

6

|

|

|

7

|

+

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

7

8

|

pub struct Position {

|

|

8

9

|

pub x: usize,

|

|

9

10

|

pub y: usize,

|

|

@@ -35,13 +36,13 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

35

36

|

should_quit: false,

|

|

36

37

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

37

38

|

document: Document::default(),

|

|

38

|

-

cursor_position: Position

|

|

39

|

+

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

39

40

|

}

|

|

40

41

|

}

|

|

41

42

|

|

|

42

43

|

fn refresh_screen(&self) -> Result<(), std::io::Error> {

|

|

43

44

|

Terminal::cursor_hide();

|

|

44

|

-

Terminal::cursor_position(&Position

|

|

45

|

+

Terminal::cursor_position(&Position::default());

|

|

45

46

|

if self.should_quit {

|

|

46

47

|

Terminal::clear_screen();

|

|

47

48

|

println!("Goodbye.\r");

|

By deriving default for Position, we have removed the duplication of

initializing the cursor position to 0, 0. If, in the future, we would decide

to intialize Position in a different way, then we could implement default

ourselves without needint to touch any other code.

We can’t derive default for our other structs - these are too complex, Rust

can not guess the default values for all struct members.

Let’s fill the Document with some text now. We won’t worry about reading from a file just yet. Instead, we’ll hard code a “Hello, World” string into it.

|

@@ -4,3 +4,11 @@ use crate::Row;

|

|

|

4

4

|

pub struct Document {

|

|

5

5

|

rows: Vec<Row>,

|

|

6

6

|

}

|

|

7

|

+

|

|

8

|

+

impl Document {

|

|

9

|

+

pub fn open() -> Self {

|

|

10

|

+

let mut rows = Vec::new();

|

|

11

|

+

rows.push(Row::from("Hello, World!"));

|

|

12

|

+

Self { rows }

|

|

13

|

+

}

|

|

14

|

+

}

|

|

@@ -35,7 +35,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

35

35

|

Self {

|

|

36

36

|

should_quit: false,

|

|

37

37

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

38

|

-

document: Document::

|

|

38

|

+

document: Document::open(),

|

|

39

39

|

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

40

40

|

}

|

|

41

41

|

}

|

|

@@ -1,3 +1,11 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

pub struct Row {

|

|

2

|

-

string: String

|

|

3

|

-

}

|

|

2

|

+

string: String,

|

|

3

|

+

}

|

|

4

|

+

|

|

5

|

+

impl From<&str> for Row {

|

|

6

|

+

fn from(slice: &str) -> Self {

|

|

7

|

+

Self {

|

|

8

|

+

string: String::from(slice),

|

|

9

|

+

}

|

|

10

|

+

}

|

|

11

|

+

}

|

You might be wondering about the From<&str> part in the impl block for the

row. We are now not only implementing a from function, but we do so by

implementing the From trait for Row. We won’t need it in the scope of this

tutorial, but implementing a trait enables us to use certain functionalities in

a certain way. We will handle traits a bit later in even more detail, but if you

are interested now, check out this part of the

docs - we

get into for free while implementing from.

We will later implement a method to open a Document from file. At that point,

we will use default again when initializing our editor. But let’s focus on

getting our hardcoded value displayed for now.

|

@@ -11,4 +11,7 @@ impl Document {

|

|

|

11

11

|

rows.push(Row::from("Hello, World!"));

|

|

12

12

|

Self { rows }

|

|

13

13

|

}

|

|

14

|

+

pub fn row(&self, index: usize) -> Option<&Row> {

|

|

15

|

+

self.rows.get(index)

|

|

16

|

+

}

|

|

14

17

|

}

|

|

@@ -1,4 +1,5 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use crate::Document;

|

|

2

|

+

use crate::Row;

|

|

2

3

|

use crate::Terminal;

|

|

3

4

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

4

5

|

|

|

@@ -105,11 +106,19 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

105

106

|

welcome_message.truncate(width);

|

|

106

107

|

println!("{}\r", welcome_message);

|

|

107

108

|

}

|

|

109

|

+

pub fn draw_row(&self, row: &Row) {

|

|

110

|

+

let start = 0;

|

|

111

|

+

let end = self.terminal.size().width as usize;

|

|

112

|

+

let row = row.render(start, end);

|

|

113

|

+

println!("{}\r", row)

|

|

114

|

+

}

|

|

108

115

|

fn draw_rows(&self) {

|

|

109

116

|

let height = self.terminal.size().height;

|

|

110

|

-

for

|

|

117

|

+

for terminal_row in 0..height - 1 {

|

|

111

118

|

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

112

|

-

if row

|

|

119

|

+

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(terminal_row as usize) {

|

|

120

|

+

self.draw_row(row);

|

|

121

|

+

} else if terminal_row == height / 3 {

|

|

113

122

|

self.draw_welcome_message();

|

|

114

123

|

} else {

|

|

115

124

|

println!("~\r");

|

|

@@ -1,3 +1,5 @@

|

|

|

1

|

+

use std::cmp;

|

|

2

|

+

|

|

1

3

|

pub struct Row {

|

|

2

4

|

string: String,

|

|

3

5

|

}

|

|

@@ -9,3 +11,11 @@ impl From<&str> for Row {

|

|

|

9

11

|

}

|

|

10

12

|

}

|

|

11

13

|

}

|

|

14

|

+

|

|

15

|

+

impl Row {

|

|

16

|

+

pub fn render(&self, start: usize, end: usize) -> String {

|

|

17

|

+

let end = cmp::min(end, self.string.len());

|

|

18

|

+

let start = cmp::min(start, end);

|

|

19

|

+

self.string.get(start..end).unwrap_or_default().to_string()

|

|

20

|

+

}

|

|

21

|

+

}

|

Let’s unravel this change starting with Row. We have added a method called

render. We call it render, because eventually it will be responsible for a

few more things than just returning a substring. Our render method is very

user friendly as it normalizes bogus input - essentially, it returns the biggest

possible substring it can generate. We’re also routinely using

unwrap_or_default, even though it’s not necessary here, as we sanitized the

start and end parameters beforehand. What happens in the last line is that we

try to create a substring from the string and either convert it or the default

value ("") to a string. (In Rust, there is a difference between a String and

something called a str. We will get to this soon.)

In Document, we add a method to retrieve a Row at a specific index. We use

Vector’s get for this, which has the signature we need: Return None if the

index is out of bounds, or the Row if we have one.

Let’s move to Editor. In draw_rows, we first rename the variable row to

terminal_row to avoid confusion with the row we are now getting from

Document. We are then retrieving the row and displaying it. The concept here

is that Row makes sure to return to you a substring that can be displayed,

while the Editor makes sure that the terminal dimensions are met.

However, our welcome message is still displayed. We don’t want that when the

user is opening a file, so let’s add a method is_empty to our Document and

check against it in draw_rows:

|

@@ -14,4 +14,7 @@ impl Document {

|

|

|

14

14

|

pub fn row(&self, index: usize) -> Option<&Row> {

|

|

15

15

|

self.rows.get(index)

|

|

16

16

|

}

|

|

17

|

+

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

|

|

18

|

+

self.rows.is_empty()

|

|

19

|

+

}

|

|

17

20

|

}

|

|

@@ -118,7 +118,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

118

118

|

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

119

119

|

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(terminal_row as usize) {

|

|

120

120

|

self.draw_row(row);

|

|

121

|

-

} else if terminal_row == height / 3 {

|

|

121

|

+

} else if self.document.is_empty() && terminal_row == height / 3 {

|

|

122

122

|

self.draw_welcome_message();

|

|

123

123

|

} else {

|

|

124

124

|

println!("~\r");

|

You should be able to confirm that the message is no longer shown in the middle of the screen.

Next, let’s allow the user to open and display actual file. We start by changing

our Document:

|

@@ -1,4 +1,5 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use crate::Row;

|

|

2

|

+

use std::fs;

|

|

2

3

|

|

|

3

4

|

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

4

5

|

pub struct Document {

|

|

@@ -6,10 +7,15 @@ pub struct Document {

|

|

|

6

7

|

}

|

|

7

8

|

|

|

8

9

|

impl Document {

|

|

9

|

-

|

|

10

|

+

pub fn open(filename: &str ) -> Result<Self, std::io::Error> {

|

|

11

|

+

let contents = fs::read_to_string(filename)?;

|

|

10

12

|

let mut rows = Vec::new();

|

|

11

|

-

|

|

12

|

-

|

|

13

|

+

for value in contents.lines() {

|

|

14

|

+

rows.push(Row::from(value));

|

|

15

|

+

}

|

|

16

|

+

Ok(Self{

|

|

17

|

+

rows

|

|

18

|

+

})

|

|

13

19

|

}

|

|

14

20

|

pub fn row(&self, index: usize) -> Option<&Row> {

|

|

15

21

|

self.rows.get(index)

|

|

@@ -36,7 +36,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

36

36

|

Self {

|

|

37

37

|

should_quit: false,

|

|

38

38

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

39

|

-

document: Document::

|

|

39

|

+

document: Document::default(),

|

|

40

40

|

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

41

41

|

}

|

|

42

42

|

}

|

We are now using a default Document on start, and added a new method open,

which attempts to open a file and returns an error in case of a failure.

open reads the lines into our Document struct. It’s not obvious from our

code, but each row in rows will not contain the line endings \n or \r\n,

as Rust’s line() method will cut it away for us. That makes sense: We are

already handling new lines ourselves, so we wouldn’t want to handle the ones in

the file anyways.

Let’s now actually use open to open a file which will be passed to hecto by

command line:

|

@@ -1,6 +1,7 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use crate::Document;

|

|

2

2

|

use crate::Row;

|

|

3

3

|

use crate::Terminal;

|

|

4

|

+

use std::env;

|

|

4

5

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

5

6

|

|

|

6

7

|

const VERSION: &str = env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION");

|

|

@@ -33,10 +34,18 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

33

34

|

}

|

|

34

35

|

}

|

|

35

36

|

pub fn default() -> Self {

|

|

37

|

+

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

|

|

38

|

+

let document = if args.len() > 1 {

|

|

39

|

+

let file_name = &args[1];

|

|

40

|

+

Document::open(&file_name).unwrap_or_default()

|

|

41

|

+

} else {

|

|

42

|

+

Document::default()

|

|

43

|

+

};

|

|

44

|

+

|

|

36

45

|

Self {

|

|

37

46

|

should_quit: false,

|

|

38

47

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

39

|

-

document

|

|

48

|

+

document,

|

|

40

49

|

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

41

50

|

}

|

|

42

51

|

}

|

Try it out by running cargo run in contrast to cargo run Cargo.toml!

Here are a few things to observe. First, we can use if..else as a statement -

in this case, it means that the result of either block of the if statement is

bound to document. To make this work, we have to omit ; on the last line of

each block of the if, but add a ; after the last closing }. This ensures

that document is never undefined.

Since we have implemented default on Document, we can use

unwrap_or_default here. What this does is that in case open yielded an

error, a default document will be returned, the error will be discarded (we will

rectify this later though)

We are calling Document::open() only if we have more than one arg. args is

a vector which contains the command line parameters which have been passed to

our program. Per convention, args[0] is always the name of our program, so

args[1] contains the parameter we’re after - we want to use hecto (filename)

to open a file. You can pass a file name to your program by running cargo run

(filename) while you are developing.

Now you should see your screen fill up with lines of text when you run cargo

run Cargo.toml, for example.

Scrolling

Next we want to enable the user to scroll through the whole file, instead of

just being able to see the top few lines of the file. Let’s add an offset to

the editor state, which will keep track of what row of the file the user is

currently scrolled to. We are reusing the Position struct for that.

|

@@ -16,6 +16,7 @@ pub struct Editor {

|

|

|

16

16

|

should_quit: bool,

|

|

17

17

|

terminal: Terminal,

|

|

18

18

|

cursor_position: Position,

|

|

19

|

+

offset: Position,

|

|

19

20

|

document: Document,

|

|

20

21

|

}

|

|

21

22

|

|

|

@@ -47,6 +48,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

47

48

|

terminal: Terminal::default().expect("Failed to initialize terminal"),

|

|

48

49

|

document,

|

|

49

50

|

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

51

|

+

offset: Position::default(),

|

|

50

52

|

}

|

|

51

53

|

}

|

|

52

54

|

|

We initialize it with the default value. which means we’ll be scrolled to the top left of the file by default.

Now let’s have draw_row() display the correct range of lines of the file

according to the value of offset.x, and draw_rows display the correct range

of rows according to the value of offset.y.

|

@@ -118,8 +118,9 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

118

118

|

println!("{}\r", welcome_message);

|

|

119

119

|

}

|

|

120

120

|

pub fn draw_row(&self, row: &Row) {

|

|

121

|

-

let

|

|

122

|

-

let

|

|

121

|

+

let width = self.terminal.size().width as usize;

|

|

122

|

+

let start = self.offset.x;

|

|

123

|

+

let end = self.offset.x + width;

|

|

123

124

|

let row = row.render(start, end);

|

|

124

125

|

println!("{}\r", row)

|

|

125

126

|

}

|

|

@@ -127,7 +128,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

127

128

|

let height = self.terminal.size().height;

|

|

128

129

|

for terminal_row in 0..height - 1 {

|

|

129

130

|

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

130

|

-

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(terminal_row as usize) {

|

|

131

|

+

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(terminal_row as usize + self.offset.y) {

|

|

131

132

|

self.draw_row(row);

|

|

132

133

|

} else if self.document.is_empty() && terminal_row == height / 3 {

|

|

133

134

|

self.draw_welcome_message();

|

We are adding the offset to the start and to the end, to get the slice of the

string we’re after. We are also making sure that we can handle situations where

our string is not long enough to fit the screen. If the current row has ended to

the left of the current screen (which can happen if we are in a long row and

scroll to the right), the render method of Row will return an empty string.

Where do we set the value of offset? Our strategy will be to check if the

cursor has moved outside of the visible window, and if so, adjust offset so

that the cursor is just inside the visible window. We’ll put this logic in a

function called scroll, and call it right after we handled the key press.

|

@@ -79,8 +79,25 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

79

79

|

| Key::Home => self.move_cursor(pressed_key),

|

|

80

80

|

_ => (),

|

|

81

81

|

}

|

|

82

|

+

self.scroll();

|

|

82

83

|

Ok(())

|

|

83

84

|

}

|

|

85

|

+

fn scroll(&mut self) {

|

|

86

|

+

let Position { x, y } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

87

|

+

let width = self.terminal.size().width as usize;

|

|

88

|

+

let height = self.terminal.size().height as usize;

|

|

89

|

+

let mut offset = &mut self.offset;

|

|

90

|

+

if y < offset.y {

|

|

91

|

+

offset.y = y;

|

|

92

|

+

} else if y >= offset.y.saturating_add(height) {

|

|

93

|

+

offset.y = y.saturating_sub(height).saturating_add(1);

|

|

94

|

+

}

|

|

95

|

+

if x < offset.x {

|

|

96

|

+

offset.x = x;

|

|

97

|

+

} else if x >= offset.x.saturating_add(width) {

|

|

98

|

+

offset.x = x.saturating_sub(width).saturating_add(1);

|

|

99

|

+

}

|

|

100

|

+

}

|

|

84

101

|

fn move_cursor(&mut self, key: Key) {

|

|

85

102

|

let Position { mut y, mut x } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

86

103

|

let size = self.terminal.size();

|

To scroll, we need to know the width and height of the terminal and the

current position, and we want to change the values in self.offset. If we have

moved to the left or to the top, we want to set our offset to the new position

in the document. If we have scrolled too far to the right, we are subtracting

the current offset from the new position to calculate the new offset.

Now let’s allow the cursor to advance past the bottom of the screen (but not past the bottom of the file). We tackle scrolling to the right a bit later.

|

@@ -23,4 +23,7 @@ impl Document {

|

|

|

23

23

|

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

|

|

24

24

|

self.rows.is_empty()

|

|

25

25

|

}

|

|

26

|

+

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

|

|

27

|

+

self.rows.len()

|

|

28

|

+

}

|

|

26

29

|

}

|

|

@@ -101,7 +101,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

101

101

|

fn move_cursor(&mut self, key: Key) {

|

|

102

102

|

let Position { mut y, mut x } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

103

103

|

let size = self.terminal.size();

|

|

104

|

-

let height =

|

|

104

|

+

let height = self.document.len();

|

|

105

105

|

let width = size.width.saturating_sub(1) as usize;

|

|

106

106

|

match key {

|

|

107

107

|

Key::Up => y = y.saturating_sub(1),

|

You should be able to scroll through the entire file now, when you run cargo

run src/editor.rs. The handling of the last line will be a bit strange, since

we place our cursor there, but are not rendering there. This will be fixed when

we add the status bar later in this chapter. If you try to scroll back up, you

may notice the cursor isn’t being positioned properly. That is because

Position in the state no longer refers to the position of the cursor on the

screen. It refers to the position of the cursor within the text file, but we are

still passing it to cursor_position. To position the cursor on the screen, we

now have to subtract the offset from the position within the document.

|

@@ -60,7 +60,10 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

60

60

|

println!("Goodbye.\r");

|

|

61

61

|

} else {

|

|

62

62

|

self.draw_rows();

|

|

63

|

-

Terminal::cursor_position(&

|

|

63

|

+

Terminal::cursor_position(&Position {

|

|

64

|

+

x: self.cursor_position.x.saturating_sub(self.offset.x),

|

|

65

|

+

y: self.cursor_position.y.saturating_sub(self.offset.y),

|

|

66

|

+

});

|

|

64

67

|

}

|

|

65

68

|

Terminal::cursor_show();

|

|

66

69

|

Terminal::flush()

|

Now let’s fix the horizontal scrolling. The missing piece here is that we are not yet allowing the cursor to scroll past the right of the screen. We fix that symmetrical to what we did for scrolling down:

|

@@ -103,9 +103,12 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

103

103

|

}

|

|

104

104

|

fn move_cursor(&mut self, key: Key) {

|

|

105

105

|

let Position { mut y, mut x } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

106

|

-

let size = self.terminal.size();

|

|

107

106

|

let height = self.document.len();

|

|

108

|

-

let width =

|

|

107

|

+

let width = if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

108

|

+

row.len()

|

|

109

|

+

} else {

|

|

110

|

+

0

|

|

111

|

+

};

|

|

109

112

|

match key {

|

|

110

113

|

Key::Up => y = y.saturating_sub(1),

|

|

111

114

|

Key::Down => {

|

|

@@ -16,6 +16,12 @@ impl Row {

|

|

|

16

16

|

pub fn render(&self, start: usize, end: usize) -> String {

|

|

17

17

|

let end = cmp::min(end, self.string.len());

|

|

18

18

|

let start = cmp::min(start, end);

|

|

19

|

-

self.string.get(start..end).unwrap_or_default().to_string()

|

|

19

|

+

self.string.get(start..end).unwrap_or_default().to_string()

|

|

20

|

+

}

|

|

21

|

+

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

|

|

22

|

+

self.string.len()

|

|

23

|

+

}

|

|

24

|

+

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

|

|

25

|

+

self.string.is_empty()

|

|

20

26

|

}

|

|

21

27

|

}

|

All we had to do is changing the width used by move_cursor. Horizontal

scrolling does now work. In case you are wondering, it’s a best practice to

implement is_empty as soon as you have a len function. We’re not using it

for now, but Clippy pointed it out, and it was easy for us to implement.

Our scrolling code still contains a subtle bug, which we will fix after a few other improvements. Can you spot it?

Snap cursor to end of line

Now cursor_position refers to the cursor’s position within the file, not its

position on the screen. So our goal with the next few steps is to limit the

values of cursor_position to only ever point to valid positions in the file,

with the exception that we allow the cursor to point one character past the end

of a line or past the end of the file, so that the user can add new characters

at the end of a line, and new lines at the end of the file can be added easily.

We are already able to prevent the user from scrolling too far to the right or

too far down. The user is still able to move the cursor past the end of a line,

however. They can do it by moving the cursor to the end of a long line, then

moving it down to the next line, which is shorter. The cursor_position.y value

won’t change, and the cursor will be off to the right of the end of the line

it’s now on.

Let’s add some code to move_cursor() that corrects cursor_position if it

ends up past the end of the line it’s on.

|

@@ -104,7 +104,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

104

104

|

fn move_cursor(&mut self, key: Key) {

|

|

105

105

|

let Position { mut y, mut x } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

106

106

|

let height = self.document.len();

|

|

107

|

-

let width = if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

107

|

+

let mut width = if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

108

108

|

row.len()

|

|

109

109

|

} else {

|

|

110

110

|

0

|

|

@@ -128,6 +128,15 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

128

128

|

Key::End => x = width,

|

|

129

129

|

_ => (),

|

|

130

130

|

}

|

|

131

|

+

width = if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

132

|

+

row.len()

|

|

133

|

+

} else {

|

|

134

|

+

0

|

|

135

|

+

};

|

|

136

|

+

if x > width {

|

|

137

|

+

x = width;

|

|

138

|

+

}

|

|

139

|

+

|

|

131

140

|

self.cursor_position = Position { x, y }

|

|

132

141

|

}

|

|

133

142

|

fn draw_welcome_message(&self) {

|

We have to set width again, since row can have changed during the key

processing. We then set the new value of x, making sure that x does not exceed

the current row’s width.

Scrolling with Page Up and Page Down

Now that we have scrolling, let’s make the Page Up and Page Down keys scroll up or down an entire page instead of the full document.

|

@@ -102,6 +102,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

102

102

|

}

|

|

103

103

|

}

|

|

104

104

|

fn move_cursor(&mut self, key: Key) {

|

|

105

|

+

let terminal_height = self.terminal.size().height as usize;

|

|

105

106

|

let Position { mut y, mut x } = self.cursor_position;

|

|

106

107

|

let height = self.document.len();

|

|

107

108

|

let mut width = if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

@@ -122,8 +123,20 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

122

123

|

x = x.saturating_add(1);

|

|

123

124

|

}

|

|

124

125

|

}

|

|

125

|

-

Key::PageUp =>

|

|

126

|

-

|

|

126

|

+

Key::PageUp => {

|

|

127

|

+

y = if y > terminal_height {

|

|

128

|

+

y - terminal_height

|

|

129

|

+

} else {

|

|

130

|

+

0

|

|

131

|

+

}

|

|

132

|

+

}

|

|

133

|

+

Key::PageDown => {

|

|

134

|

+

y = if y.saturating_add(terminal_height) < height {

|

|

135

|

+

y + terminal_height as usize

|

|

136

|

+

} else {

|

|

137

|

+

height

|

|

138

|

+

}

|

|

139

|

+

}

|

|

127

140

|

Key::Home => x = 0,

|

|

128

141

|

Key::End => x = width,

|

|

129

142

|

_ => (),

|

We were able to get rid of unnecessary saturating arithmetics. Why? For example,

y and height have the same type. If y.saturating_add(terminal_height) is

less than height, then y + terminal_height is also less than height.

If we try this out now, we can see that we still have some issues with the last line. Instead of moving to the next screen on Page Down, our cursor lands at the empty row at the bottom. We’ll fix this at the end of this chapter

- but before we do, let’s complete our cursor navigation in this file.

Moving left at the start of a line

We want to allow the user to press ← at the beginning of the line to move to the end of the previous line.

|

@@ -117,7 +117,18 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

117

117

|

y = y.saturating_add(1);

|

|

118

118

|

}

|

|

119

119

|

}

|

|

120

|

-

Key::Left =>

|

|

120

|

+

Key::Left => {

|

|

121

|

+

if x > 0 {

|

|

122

|

+

x -= 1;

|

|

123

|

+

} else if y > 0 {

|

|

124

|

+

y -= 1;

|

|

125

|

+

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(y) {

|

|

126

|

+

x = row.len();

|

|

127

|

+

} else {

|

|

128

|

+

x = 0;

|

|

129

|

+

}

|

|

130

|

+

}

|

|

131

|

+

}

|

|

121

132

|

Key::Right => {

|

|

122

133

|

if x < width {

|

|

123

134

|

x = x.saturating_add(1);

|

We make sure they aren’t on the very first line before we move them up a line.

We don’t need to use saturating_sub any more, as we check explicitly if the

value we want to subtract from is bigger than 0.

Moving right at the end of a line

Similarly, let’s allow the user to press → at the end of a line to go to the beginning of the next line.

|

@@ -131,7 +131,10 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

131

131

|

}

|

|

132

132

|

Key::Right => {

|

|

133

133

|

if x < width {

|

|

134

|

-

x

|

|

134

|

+

x += 1;

|

|

135

|

+

} else if y < height {

|

|

136

|

+

y += 1;

|

|

137

|

+

x = 0;

|

|

135

138

|

}

|

|

136

139

|

}

|

|

137

140

|

Key::PageUp => {

|

Here we have to make sure they’re not at the end of the file before moving down

a line. We were also able to remove saturated_add here. height and y are

of the same type, so if y is smaller than height, then we have enough room

to add 1 to it.

Fix scrolling

Now, let’s focus on the bug that I hinted at above. To reproduce it, save the

following as a text file and open it with hecto:

aaa

äää

y̆y̆y̆

❤❤❤

When you scroll around in that file, you will notice that only the first line scrolls correctly to the right, all other lines let you scroll past the end of the line.

One of our first steps in this tutorial was to observe the bytes returned to us on every key press. We observed that German Umlauts such as ä return multiple bytes, and that’s exactly what’s causing the bug.

Let’s observe the behavior in more detail. Don’t worry, we’re not going to revert our code to observe key presses again, instead we’re going to head over to the Rust playground and paste in the following code:

fn main() {

dbg!("aaa".to_string().len());

dbg!("äää".to_string().len());

dbg!("y̆y̆y̆".to_string().len());

dbg!("❤❤❤".to_string().len());

}

dbg! is a macro which is useful for quick and dirty debugging, it prints out

the current value of what you give in, and more. Here’s what it returns for that

code:

[src/main.rs:2] "aaa".to_string().len() = 3

[src/main.rs:3] "äää".to_string().len() = 6

[src/main.rs:4] "y̆y̆y̆".to_string().len() = 9

[src/main.rs:5] "❤❤❤".to_string().len() = 9

We can see now that the length of the string can be bigger than what we thought would be the length of the string, as some characters simply take up more than one byte, or are a composition of more than one character. For instance, the Female Scientist Emoji (👩🔬) is a combination of the Woman Emoji (👩) and the Microscope Emoji (🔬). Wrong handling of these emojis can lead to interesting results.

So what is the length of a row for us? Fundamentally, it’s one element on the screen that our mouse can move over. That is called a Grapheme, and Rust, unlike some other languages, does not support Graphemes by default. That means that we either need to do the coding ourselves, or we use a crate which does this for us. Since I’m not in the mood for reinventing the wheel, let’s use a crate for that.

|

@@ -7,4 +7,5 @@ edition = "2018"

|

|

|

7

7

|

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

|

|

8

8

|

|

|

9

9

|

[dependencies]

|

|

10

|

-

termion = "1"

|

|

10

|

+

termion = "1"

|

|

11

|

+

unicode-segmentation = "1"

|

|

@@ -1,4 +1,5 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use std::cmp;

|

|

2

|

+

use unicode_segmentation::UnicodeSegmentation;

|

|

2

3

|

|

|

3

4

|

pub struct Row {

|

|

4

5

|

string: String,

|

|

@@ -16,10 +17,18 @@ impl Row {

|

|

|

16

17

|

pub fn render(&self, start: usize, end: usize) -> String {

|

|

17

18

|

let end = cmp::min(end, self.string.len());

|

|

18

19

|

let start = cmp::min(start, end);

|

|

19

|

-

|

|

20

|

+

let mut result = String::new();

|

|

21

|

+

for grapheme in self.string[..]

|

|

22

|

+

.graphemes(true)

|

|

23

|

+

.skip(start)

|

|

24

|

+

.take(end - start)

|

|

25

|

+

{

|

|

26

|

+

result.push_str(grapheme);

|

|

27

|

+

}

|

|

28

|

+

result

|

|

20

29

|

}

|

|

21

30

|

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

|

|

22

|

-

self.string.

|

|

31

|

+

self.string[..].graphemes(true).count()

|

|

23

32

|

}

|

|

24

33

|

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

|

|

25

34

|

self.string.is_empty()

|

We have introduced two changes. In both cases, we are performing graphemes()

on the slice of the full String (indicated by [..]) and then use that iterator.

In the case of len(), we are calling count() on the iterator, which tells us

how many graphemes there are. In case of render, we are now starting to build

our own string instead of using the built-in methods. For that, we skip the

first graphemes (the ones to the left of the screen), and we only take

end-start many graphemes (the visible portion of the row). These graphemes are

then pushed into the return value.

While this works, the performance is not optimal. count actually goes through

the whole iterator and then returns the value. This means that for every visible

row, we are repeatedly counting the length of the full row. Let’s keep track of

the length ourselves instead.

|

@@ -3,13 +3,17 @@ use unicode_segmentation::UnicodeSegmentation;

|

|

|

3

3

|

|

|

4

4

|

pub struct Row {

|

|

5

5

|

string: String,

|

|

6

|

+

len: usize,

|

|

6

7

|

}

|

|

7

8

|

|

|

8

9

|

impl From<&str> for Row {

|

|

9

10

|

fn from(slice: &str) -> Self {

|

|

10

|

-

Self {

|

|

11

|

+

let mut row = Self {

|

|

11

12

|

string: String::from(slice),

|

|

12

|

-

|

|

13

|

+

len: 0,

|

|

14

|

+

};

|

|

15

|

+

row.update_len();

|

|

16

|

+

row

|

|

13

17

|

}

|

|

14

18

|

}

|

|

15

19

|

|

|

@@ -28,9 +32,12 @@ impl Row {

|

|

|

28

32

|

result

|

|

29

33

|

}

|

|

30

34

|

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

|

|

31

|

-

self.

|

|

35

|

+

self.len

|

|

32

36

|

}

|

|

33

37

|

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

|

|

34

|

-

self.

|

|

38

|

+

self.len == 0

|

|

39

|

+

}

|

|

40

|

+

fn update_len(&mut self) {

|

|

41

|

+

self.len = self.string[..].graphemes(true).count();

|

|

35

42

|

}

|

|

36

43

|

}

|

Now we only have to remember to call update_len whenever our row changes.

Scrolling works now - or does it? Turns out we have to jump through one more

hoop to get all of it right.

Rendering Tabs

If you try opening a file with tabs, you’ll notice that the tab character takes up a width of 8 columns or so. As you probably know, there is a long and ongoing debate of whether or not to use tabs or spaces for indentation. Honestly, I don’t care, I have always a sufficiently advanced editor that could just roll with any indentation type you throw at it. If I was forced to pick a side, I would pick “spaces”, though, because I find the “pros” for tabs not very convincing - but that’s a different matter. What matters, though, is that we are simply replacing tabs with one space for the sake of this tutorial. That’s enough for our purpose, as in the Rust ecosystem, you will rarely encounter tabs.

Let’s replace our tabs with spaces now.

|

@@ -27,7 +27,11 @@ impl Row {

|

|

|

27

27

|

.skip(start)

|

|

28

28

|

.take(end - start)

|

|

29

29

|

{

|

|

30

|

-

|

|

30

|

+

if grapheme == "\t" {

|

|

31

|

+

result.push_str(" ");

|

|

32

|

+

} else {

|

|

33

|

+

result.push_str(grapheme);

|

|

34

|

+

}

|

|

31

35

|

}

|

|

32

36

|

result

|

|

33

37

|

}

|

That’s it - we have finally solved all the edge cases we care about. Now let’s tackle one last issue which has been bugging us for quite some time: Let’s fix that last line.

Status bar

The last thing we’ll add before finally getting to text editing is a status bar. This will show useful information such as the filename, how many lines are in the file, and what line you’re currently on. Later we’ll add a marker that tells you whether the file has been modified since it was last saved, and we’ll also display the filetype when we implement syntax highlighting.

First we’ll simply make room for a two-line status bar at the bottom of the screen. We will now also fix the issues we have with the rendering of the last line.

|

@@ -185,7 +185,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

185

185

|

}

|

|

186

186

|

fn draw_rows(&self) {

|

|

187

187

|

let height = self.terminal.size().height;

|

|

188

|

-

for terminal_row in 0..height

|

|

188

|

+

for terminal_row in 0..height {

|

|

189

189

|

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

190

190

|

if let Some(row) = self.document.row(terminal_row as usize + self.offset.y) {

|

|

191

191

|

self.draw_row(row);

|

|

@@ -19,7 +19,7 @@ impl Terminal {

|

|

|

19

19

|

Ok(Self {

|

|

20

20

|

size: Size {

|

|

21

21

|

width: size.0,

|

|

22

|

-

height: size.1,

|

|

22

|

+

height: size.1.saturating_sub(2),

|

|

23

23

|

},

|

|

24

24

|

_stdout: stdout().into_raw_mode()?,

|

|

25

25

|

})

|

You should now be able to confirm that two lines are cleared at the bottom and that Page Up and Down works as expected.

Notice how with this change, our text viewer works just fine, including scrolling and cursor movement, and the last lines where our status bar will be are left alone by the rest of the display code.

To make the status bar stand out, we’re going to display it colored. termion

takes care of the corresponding escape sequences for us, so we don’t have to do

this manually. The corresponding escape sequence is the m command (Select

Graphic Rendition). The

VT100 User Guide doesn’t

document color, so let’s turn to the Wikipedia article on ANSI escape

codes. It includes a large

table containing all the different argument codes you can use with the m

command on various terminals. It also includes the ANSI color table with the 8

foreground/background colors available.

We’re going to use termion’s capability to provide RGB colors, which fall back

to simpler colors in case they are not supported by the current terminal.

|

@@ -2,8 +2,10 @@ use crate::Document;

|

|

|

2

2

|

use crate::Row;

|

|

3

3

|

use crate::Terminal;

|

|

4

4

|

use std::env;

|

|

5

|

+

use termion::color;

|

|

5

6

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

6

7

|

|

|

8

|

+

const STATUS_BG_COLOR: color::Rgb = color::Rgb(239, 239, 239);

|

|

7

9

|

const VERSION: &str = env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION");

|

|

8

10

|

|

|

9

11

|

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

@@ -60,6 +62,8 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

60

62

|

println!("Goodbye.\r");

|

|

61

63

|

} else {

|

|

62

64

|

self.draw_rows();

|

|

65

|

+

self.draw_status_bar();

|

|

66

|

+

self.draw_message_bar();

|

|

63

67

|

Terminal::cursor_position(&Position {

|

|

64

68

|

x: self.cursor_position.x.saturating_sub(self.offset.x),

|

|

65

69

|

y: self.cursor_position.y.saturating_sub(self.offset.y),

|

|

@@ -196,6 +200,15 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

196

200

|

}

|

|

197

201

|

}

|

|

198

202

|

}

|

|

203

|

+

fn draw_status_bar(&self) {

|

|

204

|

+

let spaces = " ".repeat(self.terminal.size().width as usize);

|

|

205

|

+

Terminal::set_bg_color(STATUS_BG_COLOR);

|

|

206

|

+

println!("{}\r", spaces);

|

|

207

|

+

Terminal::reset_bg_color();

|

|

208

|

+

}

|

|

209

|

+

fn draw_message_bar(&self) {

|

|

210

|

+

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

211

|

+

}

|

|

199

212

|

}

|

|

200

213

|

|

|

201

214

|

fn die(e: std::io::Error) {

|

|

@@ -3,6 +3,7 @@ use std::io::{self, stdout, Write};

|

|

|

3

3

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

4

4

|

use termion::input::TermRead;

|

|

5

5

|

use termion::raw::{IntoRawMode, RawTerminal};

|

|

6

|

+

use termion::color;

|

|

6

7

|

|

|

7

8

|

pub struct Size {

|

|

8

9

|

pub width: u16,

|

|

@@ -59,4 +60,10 @@ impl Terminal {

|

|

|

59

60

|

pub fn clear_current_line() {

|

|

60

61

|

print!("{}", termion::clear::CurrentLine);

|

|

61

62

|

}

|

|

63

|

+

pub fn set_bg_color(color: color::Rgb) {

|

|

64

|

+

print!("{}", color::Bg(color));

|

|

65

|

+

}

|

|

66

|

+

pub fn reset_bg_color() {

|

|

67

|

+

print!("{}", color::Bg(color::Reset));

|

|

68

|

+

}

|

|

62

69

|

}

|

Note: On some terminals, such as on Mac, the termion colors won’t be displayed properly. For the sake of the tutorial, you could then use

termion::style::Invert. See this github issue for details.

We have started by extending our terminal with a few new functions, to set and

to reset the background color. We need to reset the colors after we use them,

otherwise the rest of the screen will also be rendered in the same color.

We use that functionality in editor to draw a line of empty spaces where our

status bar will be. We have also added a function to draw the message bar below

the status bar, but we leave it empty for now.

We want to display the file name next. Let’s adjust our Document to have an

optional file name, and set it in open. We’re also going to prepare the

Terminal to set and reset the foreground color.

|

@@ -4,17 +4,19 @@ use std::fs;

|

|

|

4

4

|

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

5

5

|

pub struct Document {

|

|

6

6

|

rows: Vec<Row>,

|

|

7

|

+

file_name: Option<String>,

|

|

7

8

|

}

|

|

8

9

|

|

|

9

10

|

impl Document {

|

|

10

|

-

|

|

11

|

+

pub fn open(filename: &str) -> Result<Self, std::io::Error> {

|

|

11

12

|

let contents = fs::read_to_string(filename)?;

|

|

12

13

|

let mut rows = Vec::new();

|

|

13

14

|

for value in contents.lines() {

|

|

14

15

|

rows.push(Row::from(value));

|

|

15

16

|

}

|

|

16

|

-

Ok(Self{

|

|

17

|

-

rows

|

|

17

|

+

Ok(Self {

|

|

18

|

+

rows,

|

|

19

|

+

file_name: Some(filename.to_string()),

|

|

18

20

|

})

|

|

19

21

|

}

|

|

20

22

|

pub fn row(&self, index: usize) -> Option<&Row> {

|

|

@@ -1,9 +1,9 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use crate::Position;

|

|

2

2

|

use std::io::{self, stdout, Write};

|

|

3

|

+

use termion::color;

|

|

3

4

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

4

5

|

use termion::input::TermRead;

|

|

5

6

|

use termion::raw::{IntoRawMode, RawTerminal};

|

|

6

|

-

use termion::color;

|

|

7

7

|

|

|

8

8

|

pub struct Size {

|

|

9

9

|

pub width: u16,

|

|

@@ -66,4 +66,10 @@ impl Terminal {

|

|

|

66

66

|

pub fn reset_bg_color() {

|

|

67

67

|

print!("{}", color::Bg(color::Reset));

|

|

68

68

|

}

|

|

69

|

+

pub fn set_fg_color(color: color::Rgb) {

|

|

70

|

+

print!("{}", color::Fg(color));

|

|

71

|

+

}

|

|

72

|

+

pub fn reset_fg_color() {

|

|

73

|

+

print!("{}", color::Fg(color::Reset));

|

|

74

|

+

}

|

|

69

75

|

}

|

Note that we have not used a String as a type for the file name, but an

Option, to indicate that we either have a filename or None, in case no file

name is set.

Now we’re ready to display some information in the status bar. We’ll display up to 20 characters of the filename, followed by the number of lines in the file. If there is no filename, we’ll display [No Name] instead.

|

@@ -4,7 +4,7 @@ use std::fs;

|

|

|

4

4

|

#[derive(Default)]

|

|

5

5

|

pub struct Document {

|

|

6

6

|

rows: Vec<Row>,

|

|

7

|

-

file_name: Option<String>,

|

|

7

|

+

pub file_name: Option<String>,

|

|

8

8

|

}

|

|

9

9

|

|

|

10

10

|

impl Document {

|

|

@@ -5,6 +5,7 @@ use std::env;

|

|

|

5

5

|

use termion::color;

|

|

6

6

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

7

7

|

|

|

8

|

+

const STATUS_FG_COLOR: color::Rgb = color::Rgb(63, 63, 63);

|

|

8

9

|

const STATUS_BG_COLOR: color::Rgb = color::Rgb(239, 239, 239);

|

|

9

10

|

const VERSION: &str = env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION");

|

|

10

11

|

|

|

@@ -201,13 +202,26 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

201

202

|

}

|

|

202

203

|

}

|

|

203

204

|

fn draw_status_bar(&self) {

|

|

204

|

-

let

|

|

205

|

+

let mut status;

|

|

206

|

+

let width = self.terminal.size().width as usize;

|

|

207

|

+

let mut file_name = "[No Name]".to_string();

|

|

208

|

+

if let Some(name) = &self.document.file_name {

|

|

209

|

+

file_name = name.clone();

|

|

210

|

+

file_name.truncate(20);

|

|

211

|

+

}

|

|

212

|

+

status = format!("{} - {} lines", file_name, self.document.len());

|

|

213

|

+

if width > status.len() {

|

|

214

|

+

status.push_str(&" ".repeat(width - status.len()));

|

|

215

|

+

}

|

|

216

|

+

status.truncate(width);

|

|

205

217

|

Terminal::set_bg_color(STATUS_BG_COLOR);

|

|

206

|

-

|

|

207

|

-

|

|

218

|

+

Terminal::set_fg_color(STATUS_FG_COLOR);

|

|

219

|

+

println!("{}\r", status);

|

|

220

|

+

Terminal::reset_fg_color();

|

|

221

|

+

Terminal::reset_bg_color();;

|

|

208

222

|

}

|

|

209

|

-

|

|

210

|

-

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

223

|

+

fn draw_message_bar(&self) {

|

|

224

|

+

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

211

225

|

}

|

|

212

226

|

}

|

|

213

227

|

|

We make sure to cut the status string short in case it doesn’t fit inside the width of the window. Notice how we still use code that draws spaces up to the end of the screen, so that the entire status bar has a white background.

We are using a new macro here, format!. It’s similar to print! and

println!, without actually printing something out to the screen.

Now let’s show the current line number, and align it to the right edge of the screen.

|

@@ -210,9 +210,17 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

210

210

|

file_name.truncate(20);

|

|

211

211

|

}

|

|

212

212

|

status = format!("{} - {} lines", file_name, self.document.len());

|

|

213

|

-

|

|

214

|

-

|

|

213

|

+

|

|

214

|

+

let line_indicator = format!(

|

|

215

|

+

"{}/{}",

|

|

216

|

+

self.cursor_position.y.saturating_add(1),

|

|

217

|

+

self.document.len()

|

|

218

|

+

);

|

|

219

|

+

let len = status.len() + line_indicator.len();

|

|

220

|

+

if width > len {

|

|

221

|

+

status.push_str(&" ".repeat(width - len));

|

|

215

222

|

}

|

|

223

|

+

status = format!("{}{}", status, line_indicator);

|

|

216

224

|

status.truncate(width);

|

|

217

225

|

Terminal::set_bg_color(STATUS_BG_COLOR);

|

|

218

226

|

Terminal::set_fg_color(STATUS_FG_COLOR);

|

The current line is stored in cursor_position.y, which we add 1 to since the

position is 0-indexed. We are subtracting the length of the new part of the

status bar from the number of spaces we want to produce, and add it to the final

formatted string.

Status message

We’re going to add one more line below our status bar. This will be for

displaying messages to the user, and prompting the user for input when doing a

search, for example. We’ll store the current message in a struct called

StatusMessage, which we’ll put in the editor state. We’ll also store a

timestamp for the message, so that we can erase it a few seconds after it’s been

displayed.

|

@@ -2,6 +2,8 @@ use crate::Document;

|

|

|

2

2

|

use crate::Row;

|

|

3

3

|

use crate::Terminal;

|

|

4

4

|

use std::env;

|

|

5

|

+

use std::time::Duration;

|

|

6

|

+

use std::time::Instant;

|

|

5

7

|

use termion::color;

|

|

6

8

|

use termion::event::Key;

|

|

7

9

|

|

|

@@ -15,12 +17,26 @@ pub struct Position {

|

|

|

15

17

|

pub y: usize,

|

|

16

18

|

}

|

|

17

19

|

|

|

20

|

+

struct StatusMessage {

|

|

21

|

+

text: String,

|

|

22

|

+

time: Instant,

|

|

23

|

+

}

|

|

24

|

+

impl StatusMessage {

|

|

25

|

+

fn from(message: String) -> Self {

|

|

26

|

+

Self {

|

|

27

|

+

time: Instant::now(),

|

|

28

|

+

text: message,

|

|

29

|

+

}

|

|

30

|

+

}

|

|

31

|

+

}

|

|

32

|

+

|

|

18

33

|

pub struct Editor {

|

|

19

34

|

should_quit: bool,

|

|

20

35

|

terminal: Terminal,

|

|

21

36

|

cursor_position: Position,

|

|

22

37

|

offset: Position,

|

|

23

38

|

document: Document,

|

|

39

|

+

status_message: StatusMessage,

|

|

24

40

|

}

|

|

25

41

|

|

|

26

42

|

impl Editor {

|

|

@@ -39,9 +55,16 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

39

55

|

}

|

|

40

56

|

pub fn default() -> Self {

|

|

41

57

|

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

|

|

58

|

+

let mut initial_status = String::from("HELP: Ctrl-Q = quit");

|

|

42

59

|

let document = if args.len() > 1 {

|

|

43

60

|

let file_name = &args[1];

|

|

44

|

-

Document::open(&file_name)

|

|

61

|

+

let doc = Document::open(&file_name);

|

|

62

|

+

if doc.is_ok() {

|

|

63

|

+

doc.unwrap()

|

|

64

|

+

} else {

|

|

65

|

+

initial_status = format!("ERR: Could not open file: {}", file_name);

|

|

66

|

+

Document::default()

|

|

67

|

+

}

|

|

45

68

|

} else {

|

|

46

69

|

Document::default()

|

|

47

70

|

};

|

|

@@ -52,6 +75,7 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

52

75

|

document,

|

|

53

76

|

cursor_position: Position::default(),

|

|

54

77

|

offset: Position::default(),

|

|

78

|

+

status_message: StatusMessage::from(initial_status),

|

|

55

79

|

}

|

|

56

80

|

}

|

|

57

81

|

|

|

@@ -230,6 +254,12 @@ impl Editor {

|

|

|

230

254

|

}

|

|

231

255

|

fn draw_message_bar(&self) {

|

|

232

256

|

Terminal::clear_current_line();

|

|

257

|

+

let message = &self.status_message;

|

|

258

|

+

if Instant::now() - message.time < Duration::new(5, 0) {

|

|

259

|

+

let mut text = message.text.clone();

|

|

260

|

+

text.truncate(self.terminal.size().width as usize);

|

|

261

|

+

print!("{}", text);

|

|

262

|

+

}

|

|

233

263

|

}

|

|

234

264

|

}

|

|

235

265

|

|

We initialize status_message to a help message with the key bindings. We also

take the opportunity and set the status message to an error if we can’t open the

file, something that we silently ignored before. To do that, we have to

rearrange the code to open a document a bit, so that the correct doc is loaded

and the correct status message is set.

Now that we have a status message to display, we can modify the

draw_message_bar() function.

First we clear the message bar with Terminal::clear_current_line();. We did

not need to do that for the status bar, since we are always overwriting the

full line on every render. Then we make sure the message will fit the width of

the screen, and then display the message, but only if the message is less than 5

seconds old.

This means that we keep the old status message around, even if we are no longer displaying it. That is ok, since that data structure is small anyways and is not designed to grow over time.

When you start up the program now, you should see the help message at the bottom. It will disappear when you press a key after 5 seconds. Remember, we only refresh the screen after each key press.

In the next chapter, we will turn our text viewer into a text editor, allowing the user to insert and delete characters and save their changes to disk.

Conclusion

In this chapter, all the refactoring of the previous chapters has paid off, as we where able to extend our editor effortlessly

I hope that, like in the last chapter, you are looking at your new text viewer with pride. It’s coming along! Let’s focus on editing text in next chapter.