Previous chapter - Overview - Appendices - Next Chapter

Let’s try and read key presses from the user. Remove the line with “Hello,

world” from main and change your code as follows:

|

@@ -1,3 +1,7 @@

|

|

|

1

|

+

use std::io::{self, Read};

|

|

1

2

|

fn main() {

|

|

2

|

-

|

|

3

|

+

for b in io::stdin().bytes() {

|

|

4

|

+

let c = b.unwrap() as char;

|

|

5

|

+

println!("{}", c);

|

|

6

|

+

}

|

|

3

7

|

}

|

Play around with that program and try to find out how it works. To stop it, press Ctrl-C.

First, we are using use to import things into our program. We would like to do

something with the input/output of the system, io in short. So we use use

std::io::{self, Read}, which imports io for us and is short for:

use std::io;

use std::io::Read;

After this, we are able to use io in our code, and bringing Read into our

code enables us to use bytes(). Try running your code without importing

Read, and the compiler will exit with an error explaining that Read needs,

in fact, to be in scope, because it brings the implementation of bytes with

it. This concept is called a trait, and we will take a deeper look at traits

later in this tutorial. The documentation on

traits is definitely

something to add on your reading list!

If you are new to Rust, don’t worry. We have a bit of learning to do in this chapter, but future code additions won’t bring as many new concepts at once as this one. Also, some of the concepts get clearer as the tutorial progresses, so don’t worry if you don’t understand everything at once.

The first line in main does a lot of things at once, which can be summarized

as “For every byte you can read from the keyboard, bind it to b and execute

the following block”.

Let’s unravel that line now. io::stdin() means that we want to call a method

called stdin from io - io being one of the things we just imported.

stdin represents the Standard Input

Stream,

which, simply put, gives you access to everything that can be put into your

program.

Calling bytes() on io::stdin() returns something we can iterate over, or

in other words: Something which lets us perform the same task on a series of

elements. In Rust, same as many other languages, this concept is called an

Iterator.

Using an Iterator allows us to build a loop with for..in. With for..in in

combination with bytes(), we are asking rust to read byte from the standard

input into the variable b, and to keep doing it until there are no more bytes

to read. The two lines after for..in print out each character - we will

explain unwrap and println! later - and return if there is nothing more to

read.

When you run ./hecto, your terminal gets hooked up to the standard input, and

so your keyboard input gets read into the b variable. However, by default your

terminal starts in canonical mode, also called cooked mode. In this

mode, keyboard input is only sent to your program when the user presses

Enter. This is useful for many programs: it lets the user type in a

line of text, use Backspace to fix errors until they get their input

exactly the way they want it, and finally press Enter to send it to

the program. But it does not work well for programs with more complex user

interfaces, like text editors. We want to process each key press as it comes in,

so we can respond to it immediately.

To exit the above program, press Ctrl-D to tell Rust that it’s reached the end of file. Or you can always press Ctrl-C to signal the process to terminate immediately.

What we want is raw mode. Fortunately, there are external libraries available to set the terminal to raw mode. Libraries in Rust are called Crates - if you want to read up on those, here’s the link to the docs. Like many other programming languages, Rust comes with a lean core and relies on crates to extend its functionality. In this tutorial, we will sometimes do things manually first before switching to external functionality, and sometimes we jump directly to the library function.

Press q to quit?

To demonstrate how canonical mode works, we’ll have the program exit when it reads a q key press from the user.

|

@@ -3,5 +3,8 @@ fn main() {

|

|

|

3

3

|

for b in io::stdin().bytes() {

|

|

4

4

|

let c = b.unwrap() as char;

|

|

5

5

|

println!("{}", c);

|

|

6

|

+

if c == 'q' {

|

|

7

|

+

break;

|

|

8

|

+

}

|

|

6

9

|

}

|

|

7

10

|

}

|

Note that in Rust, characters require single quotes, ' , instead of double

quotes, ", to work!

To quit this program, you will have to type a line of text that includes a q

in it, and then press enter. The program will quickly read the line of text one

character at a time until it reads the q, at which point the for..in loop

will stop and the program will exit. Any characters after the q will be left

unread on the input queue and not printed out. Rust discards them while exiting.

Entering raw mode by using Termion

Change your Cargo.toml as follows:

|

@@ -7,3 +7,4 @@ edition = "2018"

|

|

|

7

7

|

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

|

|

8

8

|

|

|

9

9

|

[dependencies]

|

|

10

|

+

termion = "1"

|

With this, we are telling cargo that we want to have a dependency called

termion, in the version 1. Cargo follows a concept called Semantic

Versioning, where a program version usually consists of

three numbers (like 0.1.0), and by convention, no breaking change occurs as long

as the first number stays the same. That means that if you develop against

termion v1.5.0, your program will also work with termion v1.5.1 or even

termion v1.7.0. This is useful, because it means that we are getting bugfixes

and new features, but the existing features can still be used without us having

to change our code. By setting termion = "1", we are making sure we are getting

the latest version starting with 1.

Next time you run cargo build or cargo run, the new dependency, termion

will be downloaded and compiled, and the output will look something like this:

Compiling libc v0.2.62

Compiling numtoa v0.1.0

Compiling termion v1.5.3

Compiling hecto v0.1.0 (/home/philipp/repositories/hecto)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 7.83s

As you can see, termion comes with dependencies itself, and cargo downloads

and compiles them, too. You might notice that the Cargo.lock has also changed:

It now contains the exact names and versions of all packages and dependencies

which have been installed. This is helpful to avoid “Works on my machine” - bugs

if you are working on a team, where you are encountering a bug in, say, termion

v1.2.3, while your co-worker is on termion v1.2.4 and doesn’t see it.

In case you missed it in the very first chapter, this tutorial can not be completed on Windows. Termion is a dependency that is not supported on that platform - but you can run it using the Linux Subsystem.

At the time of writing this tutorial, Termion was the only option for this tutorial. Now, 2 years after the release of this tutorial, there is also a cross-platform library available: crossterm. It works differently from Termion, so you can’t directly follow this tutorial if you chose to use Windows instead of a Linux system, but if you already have a background in software programming, you might find it easy and enticing to try and adapt this for crossterm instead of Termion.

If you are looking for pointers on how to get this running with crossterm, check out this awesome hecto variant which runs on all platforms.

Now change the main.rs as follows:

|

@@ -1,5 +1,9 @@

|

|

|

1

|

-

use std::io::{self, Read};

|

|

1

|

+

use std::io::{self, stdout, Read};

|

|

2

|

+

use termion::raw::IntoRawMode;

|

|

3

|

+

|

|

2

4

|

fn main() {

|

|

5

|

+

let _stdout = stdout().into_raw_mode().unwrap();

|

|

6

|

+

|

|

3

7

|

for b in io::stdin().bytes() {

|

|

4

8

|

let c = b.unwrap() as char;

|

|

5

9

|

println!("{}", c);

|

Try it out, and you will notice that every character you type in is immediately

printed out, and as soon as you type q, the program ends.

So what did we do?

There are a few things to note here. First, we are using termion to provide

stdout, the counterpart of stdin from

above

with a function called into_raw_mode(), which we are calling. But why are we

calling that method on stdout to change how we read from stdin? The answer

is that terminals have their states controlled by the writer, not the reader.

The writer is used to draw on the screen or move the cursor, so it is also used

to change the mode as well.

Second, we are assigning the result of into_raw_mode to a variable named

_stdout but we are not doing anything with that variable. Why? Because this is

our first encounter with Rust’s Ownership

System. To

summarize a complex concept, functions can ?own certain things. Un-owned

things will be removed. into_raw_mode modifies the terminal and returns a

value which, once it is removed, will reset the terminal into canonical mode -

so we need to keep it around by binding it to _stdout. You can try it out by

removing let _stdout = - the terminal won’t stay in raw mode.

By prefixing the variable with a _, we are actually telling others reading our

code that we want to hold on to _stdout even though we are not using it. If

you have an unused variable not prefixed with _, the compiler will assume that

you have made a mistake and warn you.

Though the topic of ownership is complex, you don’t need to fully understand it at this point. Your understanding will grow over the course of this tutorial.

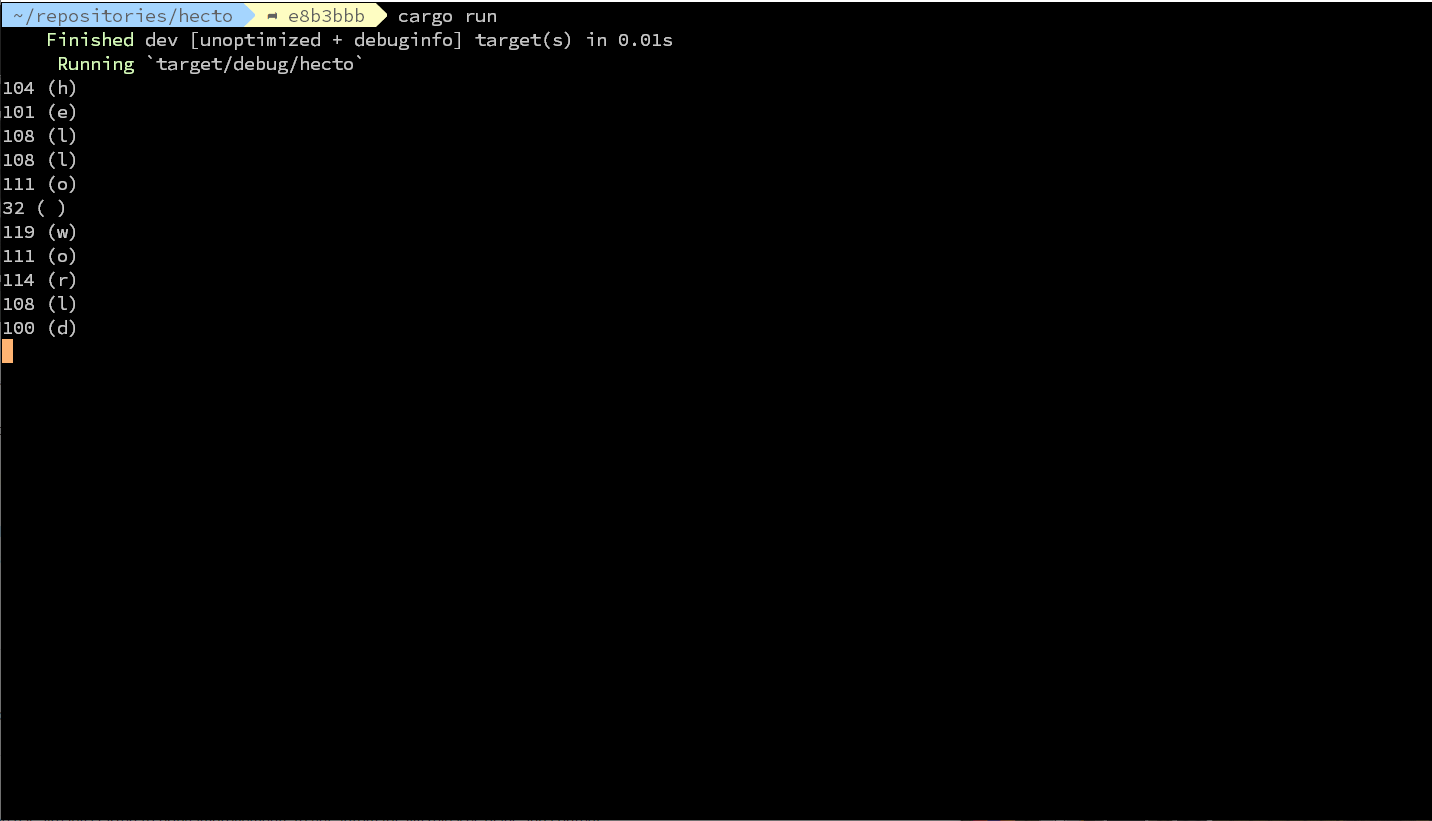

Observing key presses

To get a better idea of how input in raw mode works, let’s improve on how we print out each byte that we read.

|

@@ -5,8 +5,13 @@ fn main() {

|

|

|

5

5

|

let _stdout = stdout().into_raw_mode().unwrap();

|

|

6

6

|

|

|

7

7

|

for b in io::stdin().bytes() {

|

|

8

|

-

let

|

|

9

|

-

|

|

8

|

+

let b = b.unwrap();

|

|

9

|

+

let c = b as char;

|

|

10

|

+

if c.is_control() {

|

|

11

|

+

println!("{:?} \r", b);

|

|

12

|

+

} else {

|

|

13

|

+

println!("{:?} ({})\r", b, c);

|

|

14

|

+

}

|

|

10

15

|

if c == 'q' {

|

|

11

16

|

break;

|

|

12

17

|

}

|

Before we discuss the new functionality, let’s go through the changes quickly.

First, we are no longer only printing the character c, but also the byte code

b. In case you are wondering about b: in Rust, it is perfectly legal to

declare a variable twice. We are declaring b first in for b in..., and then

again with let b = b.unwrap(). This is called variable shadowing, and it is

immensely useful: The first value of bis not useful for us, as we only want to

work with the “unwrapped” value (I promise, we will explain that soon!).

Variable shadowing makes sure we don’t have to have to deal with two variables,

like b_wrapped and b. Try playing around with this concept by dropping the

let in let b....

By the way, the as keyword attempts to transform a primitive value into

another one, in this case a byte into a single char.

is_control() tests whether a character is a control character. Control

characters are non-printable characters that we don’t want to print to the

screen. ASCII codes 0–31 are all control characters, and 127 is also a

control character. ASCII codes 32–126 are all printable. (Check out the

ASCII table to see all of the characters.)

println! is a macro which prints its input in a single line. {} and {:?}

within the argument passed to println! are placeholders which are filled with

the remaining parameters - so println!("This is a char: {}", 'c'); will print

out “This is a char: c” . The placeholder {} is for elements for which a

printable representation is known, such as a char. {:?} is a placeholder for

elements for which a string representation is not known, but a “debug string

representation” has been implemented. To understand the difference, try swapping

around {} and {:?} and vice versa and see what happens (Understanding that

difference is not crucial for building hecto, though).

We are also printing out \r (Carriage Return) at the end of each line. This

makes sure our output is neatly printed line by line without indentation. The

carriage return moves the cursor back to the beginning of the current line

before println! adds a \n (newline), which moves the cursor down a line,

scrolling the screen if necessary. (These two distinct operations originated in

the days of typewriters and

teletypes.)

This is a very useful program. It shows us how various key presses translate into the characters we read. Most ordinary keys translate directly into the characters they represent. But try seeing what happens when you press the arrow keys, or Escape, or Page Up, or Page Down, or Home, or End, or Backspace, or Delete, or Enter. Try key combinations with Ctrl, like Ctrl-A, Ctrl-B, etc.

You’ll notice a few interesting things:

- Arrow keys, Page Up, Page Down, Home, and

End all input 3 or 4 bytes to the terminal:

27,[, and then one or two other characters. This is known as an escape sequence. All escape sequences start with a27byte. Pressing Escape sends a single27byte as input, which explains either the name of the key or the sequence. - Backspace is byte

127. - Enter is byte

13, which is a carriage return character, also known as'\r'- and not, as you might expect, a newline,'\n' - Special characters such as German umlauts also produce multiple bytes.

- Ctrl-A is

1, Ctrl-B is2, Ctrl-C is…3and doesn’t terminate the program as you might have expected. And the rest of the Ctrl key combinations seem to map the letters A–Z to the codes 1–26.

Press Ctrl-Q to quit

We now know that the Ctrl key combined with the alphabetic keys seems to map to bytes 1–26. We can use this to detect Ctrl key combinations and map them to different operations in our editor. We’ll use that to map Ctrl-Q to the quit operation.

|

@@ -1,6 +1,11 @@

|

|

|

1

1

|

use std::io::{self, stdout, Read};

|

|

2

2

|

use termion::raw::IntoRawMode;

|

|

3

3

|

|

|

4

|

+

fn to_ctrl_byte(c: char) -> u8 {

|

|

5

|

+

let byte = c as u8;

|

|

6

|

+

byte & 0b0001_1111

|

|

7

|

+

}

|

|

8

|

+

|

|

4

9

|

fn main() {

|

|

5

10

|

let _stdout = stdout().into_raw_mode().unwrap();

|

|

6

11

|

|

|

@@ -12,7 +17,7 @@ fn main() {

|

|

|

12

17

|

} else {

|

|

13

18

|

println!("{:?} ({})\r", b, c);

|

|

14

19

|

}

|

|

15

|

-

if

|

|

20

|

+

if b == to_ctrl_byte('q') {

|

|

16

21

|

break;

|

|

17

22

|

}

|

|

18

23

|

}

|

If you think that this whole bitwise-voodoo is too low-level for the task, then you are right! We are doing this now to get a better understanding about the fundamentals, but we will refactor it in the next chapter.

The to_ctrl_byte function bitwise-ANDs a character with the value 00011111,

in binary. If you are interested, you can use println!("{:#b}", b); to print

out the binary representation of the variable b (The b in {:#b} and the

variable name b are not related). Try this to see the actual bytes which are

read into our program. When you compare the output for Ctrl-Key with

the output of the key without Ctrl, you will notice that Ctrl sets

the upper 3 bits to 0. If we now remember how bitwise and works, we can see

that to_ctrl_byte does just the same.

The ASCII character set seems to be designed this way on purpose. (It is also similarly designed so that you can set and clear a bit to switch between lowercase and uppercase. If you are interested, find out which byte it is and what the impact is on combinations such as Ctrl-a in contrast to Ctrl-Shift-a.)

Error Handling

It’s time to think about how we handle errors. First, we add a die() function

that prints an error message and exits the program.

|

@@ -6,6 +6,10 @@ fn to_ctrl_byte(c: char) -> u8 {

|

|

|

6

6

|

byte & 0b0001_1111

|

|

7

7

|

}

|

|

8

8

|

|

|

9

|

+

fn die(e: std::io::Error) {

|

|

10

|

+

panic!(e);

|

|

11

|

+

}

|

|

12

|

+

|

|

9

13

|

fn main() {

|

|

10

14

|

let _stdout = stdout().into_raw_mode().unwrap();

|

|

11

15

|

|

panic! is a macro which crashes the program with an error message. Unlike

some other programming languages, Rust does not allow you to add some kind of

try..catch block around the code to catch any error that might occur. Instead,

we are propagating errors up alongside the function return values, which will

allow us to treat errors at the highest level.

This propagation works so that a function where an error could happen returns

something called a

Result,

which is a wrapper around the result we’re after, or an error. Every value in

b is originally a Result, which either holds an Ok wrapping the byte we

have read in, or an Err which wraps an Error object, indicating that something

went wrong while reading the byte. To get the value we need, we can call

unwrap, which is short for: “If we have an Ok, return the value wrapped in

it. panic if we have an Err.”

We want to control the crash ourselves instead of letting Rust panic whenever

an error occurs, because later on, we want to clear the screen before crashing,

to not leave the user with half-drawn input. For now, let’s simply check for an

error and call die, which panics for us.

Let’s implement that now.

|

@@ -14,15 +14,19 @@ fn main() {

|

|

|

14

14

|

let _stdout = stdout().into_raw_mode().unwrap();

|

|

15

15

|

|

|

16

16

|

for b in io::stdin().bytes() {

|

|

17

|

-

|

|

18

|

-

|

|

19

|

-

|

|

20

|

-

|

|

21

|

-

|

|

22

|

-

|

|

23

|

-

|

|

24

|

-

|

|

25

|

-

|

|

17

|

+

match b {

|

|

18

|

+

Ok(b) => {

|

|

19

|

+

let c = b as char;

|

|

20

|

+

if c.is_control() {

|

|

21

|

+

println!("{:?} \r", b);

|

|

22

|

+

} else {

|

|

23

|

+

println!("{:?} ({})\r", b, c);

|

|

24

|

+

}

|

|

25

|

+

if b == to_ctrl_byte('q') {

|

|

26

|

+

break;

|

|

27

|

+

}

|

|

28

|

+

}

|

|

29

|

+

Err(err) => die(err),

|

|

26

30

|

}

|

|

27

31

|

}

|

|

28

32

|

}

|

Here are a few more things to observe. We are deliberately ignoring the error

from into_raw_mode. Our error handling is mainly aimed at avoiding garbled

output, which can only occur when we are actually repeatedly writing to the

screen, so for our purposes, there is no need for any additional error handling

before our loop begins.

Then, we have introduced a new concept: match. For now, you can think about

match as a supersized if-then-else. It takes the original variable b,

which either contains the value we want wrapped in Ok, or an error wrapped in

Err. Let’s look at an easier example:

//...

match foo {

Ok(bar) => {

//...

},

Err(err) => {

//...

}

}

//...

This code can be read as: If the variable foo is an Ok value, unwrap its

contents, bind it to the variable bar and execute the following code block. In

our case, we use variable shadowing again, so that the wrapped variable b will

be unwrapped and bound to b.

We will investigate match more deeply later. Here’s the link to the docs in

case you are interested.

Conclusion

That concludes this chapter on entering raw mode. We have learned a lot about the terminal and about the fundamentals of Rust along the way. In the next chapter, we’ll do some more terminal input/output handling, and use that to draw to the screen and allow the user to move the cursor around. We will also refactor our code to be more idiomatic, but first, we need to clarify what idiomatic means.